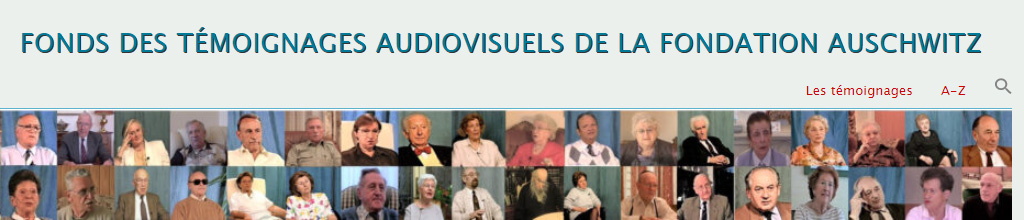

New videos (only partially in English)

Summary, abstract and full texts n° 104

Philippe Mesnard and Yannis Thanassekos: Editorial: Vingt ans après : À l'Est, du nouveau(pdf in French)(pdf in Dutch)

Dossier: L'Antifascisme revisité. Histoire – Idéologie – Mémoire

Coordinated by Carola Hähnel-Mesnard

Carola Hähnel-Mesnard: L'antifascisme - Quelle actualité ? (pdf)

I. Historical Prospects

Frediano Sessi: L’antifascisme et la résistance en Italie, 1922-1945 (pdf)

-

In its initial stages Italian antifascism was solely a movement of parliamentary protest which did not ask itself what means would really enable it to fight the new regime. The assassination of Matteotti and the definitive suppression of political parties and press and trade union freedom, together with the installation of "ultra-fascist" laws in 1926 and the establishment of the special tribunal for the defense of the State, made it clear that in future it would only be possible to oppose the fascist State through secret struggle. This led many Italians to emigrate secretly, mainly for political reasons (and not for intellectual reasons as was the case in the Third Reich). Those who secretly went abroad were socialists, communists and radical democrats, whose most noteworthy expression could be found in the "Justice and Freedom movement". These movements, together with a Catholic opposition, also existed inside Italy. Clandestine antifascism was maintained by a small minority who formed a circle of political personalities and subsequently joined the resistance. Resistance in the form of armed struggle really began on 8 September 1943, with the announcement of the armistice between Italy and the Allies, and continued until the end of the war as a struggle against both fascism and nazism.

Andreas Agocs: Restrained Revolution: Antifascist Committees in Occupied Germany, 1945-1946 (pdf)

-

This paper analyzes the role of the numerous antifascist « action groups » and committees (Antifas) that emerged in Germany during the breakdown of the NS regime and the early months of Allied occupation. The essay argues that these groups contained both elements of the mass politics of the prewar period and aspects of the more atomized politics of postwar societies. The Antifas movement was part of the larger revolutionary upheaval that transformed the social, political, and ideological structures in Europe between 1930 and 1950 and fundamentally transformed the public sphere of the interwar and war eras.Although the Antifas have been described as « initiatives with revolutionary potential », their activities, usually in cooperation with the Allies in both the east and the west, were comparatively restrained. Their establishment of workers councils made a lasting contribution to the postwar order but their attempts to become mass movements failed, not only because of Allied restrictions and prohibitions, but also owing to a lack of interest among the German population. The Antifas’ rhetoric and self-understanding evoked the paramilitary politics of the interwar period, while the experiences and social disruptions of the NS-period and the war meant that many Germans were content to leave politics and retribution to the new broad-based parties (Volksparteien) and the courts, rather than to grassroots mass movements. The idea of antifascism therefore ceased to be a revolutionary concept in the West. At the same time, the prohibition of the Antifas in the Soviet Occupation Zone paved the way for the SED’s centralized control over the GDR’s « antifascist mass organizations », which had little in common with the so-called « activists of the first hour » in the Antifas. Ultimately, therefore, the immediate postwar period can be characterized as an irrevocable process of « de-revolutionizing » the potential of antifascist activism.This paper analyzes the role of the numerous antifascist "action groups" and committees (Antifas) that emerged in Germany during the breakdown of the NS regime and the early months of Allied occupation. The essay argues that these groups contained both elements of the mass politics of the prewar period and aspects of the more atomized politics of postwar societies. The Antifas movement was part of the larger revolutionary upheaval that transformed the social, political, and ideological structures in Europe between 1930 and 1950 and fundamentally transformed the public sphere of the interwar and war eras.

Although the Antifas have been described as "initiatives with revolutionary potential", their activities, usually in cooperation with the Allies in both the East and the West, were comparatively restrained. Their establishment of Workers' Councils made a lasting contribution to the postwar order but their attempts to become mass movements failed, not only because of Allied restrictions and prohibitions, but also owing to a lack of interest among the German population. The Antifas’ rhetoric and self-understanding evoked the paramilitary politics of the interwar period, while the experiences and social disruptions of the NS-period and the war meant that many Germans were content to leave politics and retribution to the new broad-based parties (Volksparteien) and the courts, rather than to grassroots mass movements. The idea of antifascism therefore ceased to be a revolutionary concept in the West. At the same time, the prohibition of the Antifas in the Soviet Occupation Zone paved the way for the SED’s centralized control over the GDR’s "antifascist mass organizations", which had little in common with the so-called "activists of the first hour" in the Antifas. Ultimately, therefore, the immediate postwar period can be characterized as an irrevocable process of "de-revolutionizing" the potential of antifascist activism.

André Koulberg: L’antifascisme en France hier et aujourd’hui. Questions d’interprétation (pdf)

- For the last twenty years, few books dealing with antifascism have been available in France. This lack of interest is in fact a disavowal. A number of French historians specializing in the far right have questioned the relevance of the term "fascism" brandished by antifascists. Was this simply a mistake on their part? A close examination of their positions tends to show that their way of thinking and conceptualization were more coherent than first thought. In turn, these analyses enable us to question the methodology used by the historians.

- The armed resistance to Hitler by the Slovenes of Carinthia, the first such resistance inside Greater Germany and the only resistance in Austria which troubled the Nazi war machine, is distinguished by its "extra-territorial" (Yugoslav communist) military organization and its ethnic dimension. Recalling the history of the structural repression of Austria’s Slovene minority from the nineteenth century until the Nazis’ brutal policy of Germanization makes it easier to define the motives behind this movement, supported by a section of the population which was not a priori naturally inclined towards resistance. While there were only isolated acts of active resistance during the period from the Anschluss in March 1938 to the attack on Yugoslavia in April 1941, passive resistance by the Slovene minority in the form of disobedience increased. Openly persecuted with a view to ethnic homogenization, and subject to mass deportation in April 1942, many Carinthian Slovenes joined the Slovene Liberation Front and Tito’s partisans as resistance fighters. In 1945 the south of Carinthia was liberated by Tito’s Yugoslav army, which demanded the annexation of the southern part of the province, thus triggering old and new fears ("slavization" and communism). Inside Austria, whose patchy cultural memory is notorious, Carinthia’s border status and double culture make it a special case, as the antifascist remembrance of the Slovene partisans not only remains controversial for political reasons, but also seems to be permanently marked by its ethnic dimension.

II. Antifascism and the Cold War: ideology and discourses

- The history of the Association of Those Persecuted by National Socialism (Vereinigung der Verfolgten des Naziregimes) shows that all-German antifascist activities after 1945 were dependent on the context of the Cold War. While the organization was stigmatized as communist in the West, it was dissolved as unnecessary in the East. The confrontation of the two political systems overrode antifascist positions.

- In 1945, as soon as the war was over, antifascist women from 37 countries met in Paris to create the Women’s International Democratic Federation (Fédération Démocratique Internationale des Femmes), a transnational women’s organization whose stated goal was to ensure that fascism was completely crushed and the gains of the antifascist victory preserved. These women, most of whom had ties to national communist parties, were also to carry out major propaganda and defense work on behalf of the Soviet Union, in an international context marked by the coming of the Cold War. To achieve these goals, they reactivated militant practices and declarations which had already been employed in 1930’s antifascism. But they also built up a policy relating to maternity which justified their action in the public arena and led to a pacifist policy taken over by the Soviet Union in its propaganda war against the West.

III. Plurality versus uniformity: antifascist discourses in GDR

Anne Kwaschik: L’antifascisme au féminin : La RDA et Ravensbrück (pdf)

- The article aims to describe the characteristics of the "commemorative situation" of Ravensbrück at the end of the 1950’s. The only concentration camp for women, which was located in the GDR, found itself obliged to picture itself and develop on the basis of the categories used for Buchenwald, without losing its own specificities but, on the contrary, by stressing its difference. The article follows the process of negotiation over the historic elements to be retained, on the basis of two specific moments which crystallize the work of remembering: the discussions concerning the monuments which should be built inside the camp; and the literary narrative which would be acceptable as the "correct presentation" of life in the concentration camps. Thus the article examines the difficulties of the women’s camp in finding its place beside Buchenwald, stressing the ambiguous nature of this remembrance modeled on another commemoration.

- The following is a case study of an exhibition about members of the "Rote Kapelle" resistance group. Focusing on competing understandings of antifascism in the exhibition, I argue that Greta Kuckhoff was instrumental in challenging memories in both the GDR and FRG. Using concepts of the "residual" and "conjuncture", I show how the cultural turn in contemporary discussions of antifascism problematises dominant, monolithic ways of remembering.

- Discussion of the remembrance of antifascist resistance in the GDR focuses on the way in which the SED exploited it in order to stabilize its rule. The culture of the former resistance fighters who did the reminding in the so-called "Committees of antifascist resistance fighters" has hardly been noticed. The author had the opportunity to examine the autobiographical records of one of their members, Herbert Ansbach.

- When the Spanish Communist Party (PCE) was banned by the French Government in 1950, approximately 90 members went into exile in the GDR. By order of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), they were provided with all the financial and material means they needed, giving them a way of life well up to average German standards in those times. The much disputed "antifascist myth" seems to have become a reality in this case.

IV. Glorification and ideological recovery

- Youth education and children’s literature in communist East Germany promoted gendered images of communist antifascist resistance fighters, privileging masculine heroes engaged in high political and military action and marginalizing the contributions of women in supportive roles. Veteran antifascists and minority storytellers have questioned this hierarchy and complicated the antifascist master narrative.

Bill Niven: The GDR, Weimar Classicism and Resistance at Buchenwald (pdf)

- This article examines the relationship in East Germany between Buchenwald’s National Site of Warning and Commemoration and the National Research and Memorial Centre for Classical German Literature in Weimar. It argues that although they were separate organizations, they were linked by the GDR’s political and cultural authorities in an effort to prove that antifascist resistance at Buchenwald represented an expression of the same humanism as that enshrined in Germany’s classical legacy.

V. The legacy of antifascism

- Antifascism served as the backbone for the GDR’s political and ideological self-perception. Historians in the GDR defended a particular model of interpretation of fascism, Hitler and the Third Reich. The GDR proudly presented itself as the "other" and "better Germany" which had succeeded in freeing itself from the burdens of the Nazi past. After Germany’s reunification a process of political and ideological reorientation started, and the writing of history in the former East Germany underwent a drastic reconstruction. How then, and to which extent could the old idea of antifascism survive, both as a moral conviction and a historical conception? Are former GDR historians still attached to the old notions and theory of antifascism? Two trends can be distinguished. Former GDR historians generally tend to criticize the old dogmatism and political instrumentalizing which characterized the historical profession in the GDR. Most of them, however, have remained attached to a minimal consensus of antifascism as a moral conviction. Antifascism serves as the source of a moral engagement, enabling former GDR historians to defend both the historic reason for the GDR’s existence as a separate state and their personal role in it.

Other subjects

- Is it really a film which commemorates Auschwitz? Announced as "the film that commemorates Auschwitz" when it was released in 1998, La Vita è bella [Life is Beautiful] gave rise to various disputes among those involved in studying the Shoah. Among the film’s various eventual qualities and flaws, the author’s comments are based on her conviction that it is mainly about the "new fathers". Not only is it about the father-child relationship, but it also denounces fascist and racist stereotyped fantasies of virility and patriarchy. In this context, Auschwitz served only to give a dramatic motivation to the story told in the film.

Frediano Sessi: Auschwitz, Bloc 21 : Une question ouverte (pdf)

- The debate which arose in Italy over the pavilion dedicated to the Italian deportation, installed in Block 21 at Auschwitz and inaugurated in April 1980, at once took a disquieting turn. Both the National Association of Former Deportees (ANED, the legal owner of the memorial) and the Institute for the History of the Resistance and the Contemporary Era (ISREC) refused to touch the memorial. Furthermore, the memorial is a tormented work of art which reflects the wishes of those who personally lived through the drama of the deportation. But on the other hand, why not think of moving it, as it is, and exhibiting it as a work of art and remembrance in a museum in Italy, where it would be able to reach out to many young people and thus fulfill a didactic function?

- My article deals with the aesthetic and philosophical choices I made in the creation of Holocaust Portraits, Victims Perpetrators Witnesses.

The key points I make are:

1. All people were victimized by their experiences during the Holocaust. Understanding the root causes of the Holocaust requires an understanding that ordinary people were the victims of the perpetrators and the executioners of this tragedy.

2. Visual reality is fundamentally different from a literary description of reality. In my artwork I seek to enhance a contemporary viewer’s understanding of and emotional reaction to Holocaust experiences through a visual portrayal of the people who were its perpetrators' victims and witnesses.

3. Understanding why, by whom and how the Holocaust occurred is an essential part of understanding past political and moral misjudgments as we today seek to strengthen democracy, fight racism, and secure human rights for all the world’s people.

Some of our projects

Contact

Auschwitz Foundation – Remembrance of Auschwitz

Rue aux Laines 17 box 50 – B-1000 Brussels +32 (0)2 512 79 98

+32 (0)2 512 79 98 info@auschwitz.be

info@auschwitz.be

BCE/KBO Auschwitz Foundation: 0876787354

BCE/KBO Remembrance of Auschwitz: 0420667323

Office open from Monday to Friday 9:30am to 4:30pm.

Visit only by appointment.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Become a member

To become a member of Remembrance of Auschwitz ASBL, please contact us and transfer the sum of €50.00 to our account IBAN: BE55 3100 7805 1744 – BIC: BBRUBEBB with the communication: ‘Membership fee 2025’. The membership includes two issues of 2025 of our scientific journal.

DONATIONS

Donations of €40.00 or more (in one or more instalments) qualify for tax exemption for Belgian taxpayers.

In communication, please specify that it is a ‘Donation’ and mention your National Number which is required since 2024 to benefit from the tax exemption.

Subscribe

Error : Please select some lists in your AcyMailing module configuration for the field "Automatically subscribe to" and make sure the selected lists are enabled

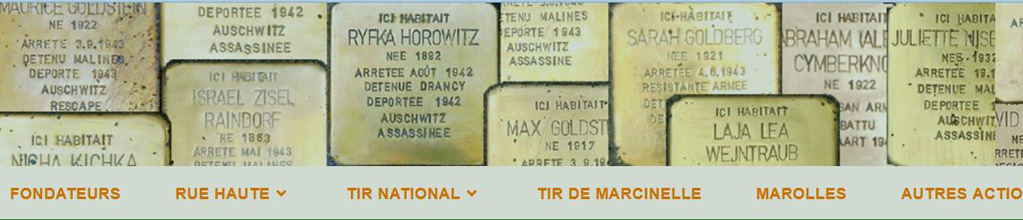

The Auschwitz Foundation was founded in 1980 by Paul Halter, an Auschwitz survivor. Replacing the Amicale Belge des Ex-Prisonniers politiques d’Auschwitz-Birkenau Camps et Prisons de Silésie, the primary objective of the Auschwitz Foundation is to study the history and memory of the victims of the Holocaust and the Nazi terror in a sustainable and systematic way. The transmission of memory and the preservation of archives concerning these events complete this goal.

The Auschwitz Foundation was founded in 1980 by Paul Halter, an Auschwitz survivor. Replacing the Amicale Belge des Ex-Prisonniers politiques d’Auschwitz-Birkenau Camps et Prisons de Silésie, the primary objective of the Auschwitz Foundation is to study the history and memory of the victims of the Holocaust and the Nazi terror in a sustainable and systematic way. The transmission of memory and the preservation of archives concerning these events complete this goal.